How the UK Government is failing in its obligation to eliminate discrimination in access to the right to food and its impact on migrant communities

By guest blogger, Leah Cowling, a participant in Tripod’s Organising for Power Programme and a volunteer at the Unity Centre Glasgow. Illustrations by Issey Medd.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Tripod.

It wasn’t long into the UK’s first lockdown that the promise of the COVID-19 pandemic as a great leveller began to ring hollow. It is now clear that the effects of the pandemic have been experienced asymmetrically across the globe – demonstrating that COVID-19 does discriminate, in that it exacerbates existing inequalities.

Described as the best vaccine against chaos, food takes on a central role in times of crisis. During the pandemic, food has been revealed to be the lynchpin upon which other rights depend. Footballer Marcus Rashford’s successful campaign to force governmental U-turns on the decision to halt free school meals highlighted one aspect of this interdependency; without nutritious food, children cannot exercise their right to education.

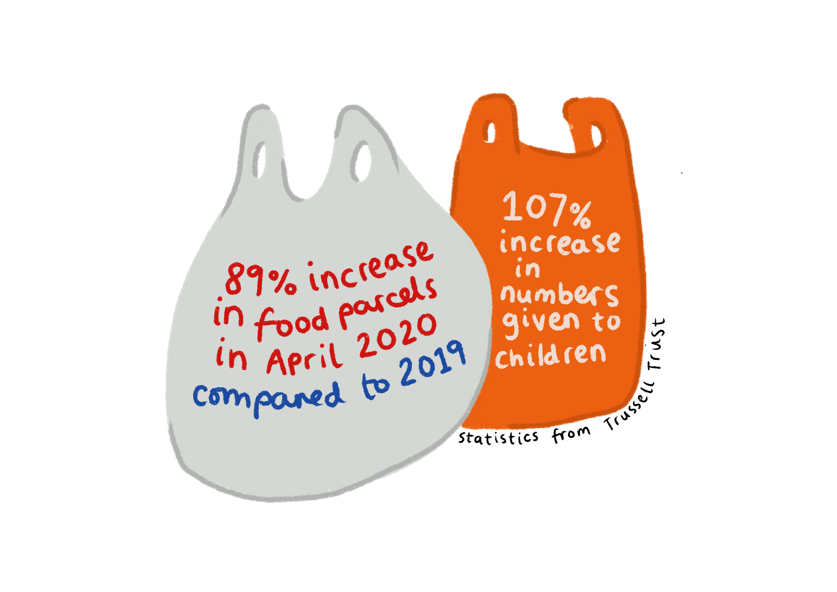

The pandemic has also demonstrated that the distribution of food is microcosmic of larger structural, political, social and economic inequalities – as the wealthy stockpiled pasta, foodbank use skyrocketed, with the independent food bank charity IFAN reporting a staggering 88% increase in use. The foodbank charity Trussell Trust reported an 89% increase in the numbers of food parcels given out in April 2020 compared to 2019, including a 107% increase in the number of parcels given to children.

While headlines were dominated by Rashford’s campaign to reinstate free school meals, the situation of food insecurity within migrant communities during COVID-19 often appeared to be an afterthought. Following the threat of a legal challenge, the free school meals policy was partially extended in April 2020 to some individuals without formal immigration status and subject to No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF) conditions, on the grounds that ‘no child should go hungry because of the immigration status of their parents’. No doubt a welcome challenge, this statement stops short of the universal acknowledgment that no one should go hungry because of their immigration status.

Consistently underreported is the experience of food insecurity by migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in the UK whose access to affordable, nutritious and culturally appropriate food has been threatened by the existence of the work ban and inadequate state support. For many, the closures of community centres, charities, churches, and support groups due to lockdown restrictions represented the severing of a crucial lifeline. Reports from March 2020 suggested that approximately 1 million undocumented migrants were plunged into severe food insecurity, with many forced to access food banks.

Numerous volunteer-run, grassroots migrant support groups, such as the Unity Centre in Glasgow, responded to the increased need with deliveries of essential food and medicine. This support was given to all those in need, including to those isolating in cramped asylum accommodation with young children. This community-led response is emblematic of a larger problem, in which support from the third sector allows the government to evade accountability for failing to protect fundamental rights.

Despite the increased visibility of widespread food insecurity during COVID-19, the effect on food insecurity among migrants in the UK has been much less discussed and appreciated. Clear delineation of the extent of this problem is challenged by a lack of data on the precise scope of the issue. This is partly because the Home Office does not have data on the exact numbers of migrants currently in the UK (a report published in 2019 estimated that there were between 800,000 and 1.2 million undocumented migrants living in the UK in 2017). But it is also partly a result of the pervasive gate-keeping that surrounds access to foodbank charity. Recipients of food parcels are often required to show proof of identity, meaning that some who are undocumented prefer unofficial methods to obtain essential food. The perception that access to food through an official foodbank may act as a form of immigration control is rife due to the UK’s hostile environment policy, which has legitimised the outsourcing of immigration control to third party brokers, such as landlords, employers, teachers, and medical professionals. This therefore contributes to the problem of migrant food insecurity being widely underappreciated, as well as acting as an additional barrier to migrants in accessing vital foodbank support.

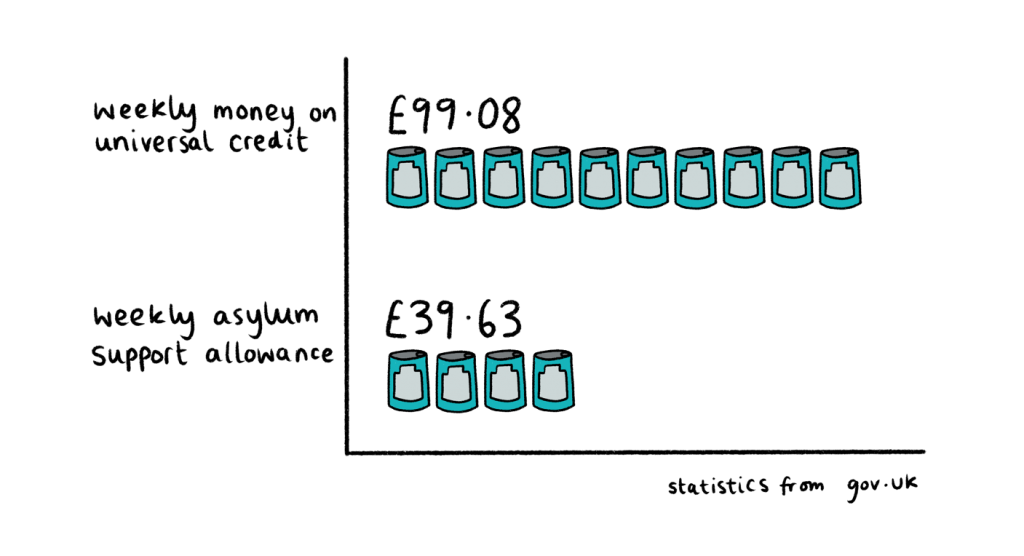

At present, individuals in receipt of asylum support under Section 95 of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 receive £37.75 a week, while those receiving Section 4 support receive £35.39. This amount is roughly half that of Universal Credit, a standard form of government support which is inaccessible to migrants who are subject to a No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF) immigration condition. For migrants in receipt of state support (many are not), this amounts to around £5 a day, and is expected to cover all essential costs including medicine, travel, toiletries, clothing, and food. The money is provided (Section 95 in cash, and Section 4 on a prepaid card) on a weekly basis. This is problematic both for budgeting purposes, as it can be difficult for recipients to buy food in large quantities, and specifically if an individual is required to isolate to comply with COVID-19 guidance.

The legal basis of the right to food

The right to food is a clearly defined legal right, articulated in a number of international human rights instruments, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) – both of which the UK is a signatory to. The right to food obliges governments to enact laws which respect, protect and fulfil the right to food, to ensure that all people can feed themselves in dignity. Crucially, the right to food is universal, applying to all individuals within a state’s borders, regardless of immigration status, and without any form of discrimination. It has been clarified by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR)’s General Comment No.20 on non-discrimination that socio-economic rights apply to everyone including ‘non-nationals, such as refugees, asylum-seekers, stateless persons, migrant workers and victims of international trafficking, regardless of legal status and documentation’. It clearly explicates the obligation incumbent on State Parties to pay particular attention to the pressing need to prevent discrimination in access to food or resources for food.

In its 2016 report on the UK, CESCR, which monitors the implementation of ICESCR, noted its concern about the lack of adequate measures ‘to address the increasing levels of food insecurity […] and the lack of adequate measures to reduce the reliance on food banks.’ Notably, while commenting on the discrimination faced by refugees, asylum seekers, refused asylum seekers and Gypsy travellers in accessing healthcare, the report omits to comment specifically on the food insecurity experienced by migrants and misses the opportunity to link the UK’s non-discrimination obligations with the right to food specifically. This omission reflects a continued trend in which the issue of food insecurity, particularly within migrant communities, is overlooked.

Considering possible solutions

Clearly, increased foodbank capacity is not a solution to rising food insecurity amongst migrant populations. Foodbank use represents the tip of the food insecurity iceberg; a symptom of pervasive structural barriers to the ability to access food in dignity. As such, we should not confuse food charity with the right to food. Most fundamentally, increased foodbank use is a clear indicator that people are struggling to meet their dietary needs with their available income, jeopardising other core rights. Additionally, the UK government cannot claim that foodbanks constitute the ‘special programmes’ of the kind suggested in paragraph 13 of General Comment No. 12, as foodbanks are distinct charitable entities which respond to gaps in governmental provision.

In recognition of the need for changes in economic accessibility of food, foodbank charity Trussell Trust recommended a £20 uplift to Universal Credit payments, which was enacted in 2020 and extended in the March 2021 budget. While the £20 uplift has reduced the reliance on foodbanks for many, this policy continues to exclude those who are unable to access Universal Credit on account of their immigration status.

A possible legal route is through incorporation of the right to food in UK law – advocated for by civil society groups, such as Sustain, Nourish Scotland and the Scottish Food Coalition. It is argued that explicit recognition of the right to food at the domestic level would help individuals articulate demands on the government, and create more legal avenues to challenge government policy.

Incorporation of the right to food in Scotland appears increasingly likely with its proposed Good Food Nation Bill, which is right to acknowledge that the main type of food insecurity in Scotland is financial, affecting mainly those whose income is insufficient to meet their nutritional needs. It is encouraging to see explicit recognition of those who were ‘already food insecure before the crisis hit, ‘including many refugees and asylum seekers who have no recourse to public funds’. However, there is no interrogation of the government’s legal obligation to identify and support groups in this category of vulnerability, nor is there suggestion of reform to the pre-existing framework for asylum support. As such the current bills on incorporation of the right to food currently insufficiently address the state-imposed barriers placed upon migrants in the UK, and must be supplemented with specific and detailed analysis of nutritional vulnerabilities experienced by migrants in Scotland.

Looking forward

An important step towards food security following the effects of COVID-19, the incorporation of the right to food in Scotland offers an opportunity to embed the right to food within a broader rights-based framework.

However, full realisation of the right to food will require appreciation of the linkages between hostile environment policies and food insecurity, as well as the multiple layers of discrimination faced by migrants in the UK. This must include calls for the removal of the NRPF immigration condition, and for increased asylum support payments in line with Universal Credit.

Looking forward, it is likely that in practice, it will be up to the courts to push for recognition of the right to food at the state level. It is increasingly evident that progress on the right to food in the UK will be led by litigation on behalf of children from migrant backgrounds – for instance in the upcoming high court case attempting to secure an 11-month year old baby’s right to vitamins, formula milk and nutritious food after exclusion from the UK government’s Healthy Start programme on Home Office eligibility grounds. In addition to litigation, progress will require going beyond human rights advocacy, to include grassroots campaigning led by those with lived experience.

An integrated, person-centred, rights-based approach to food security in a post COVID-19 landscape will require commitment to the uncontroversial statement that no one should go hungry because of their immigration status.

ABOUT OUR GUEST BLOGGER: Leah is a Human Rights LLM student and volunteer at the Unity Centre in Glasgow, which provides practical and emotional support to all those in the immigration system. She is also a volunteer with Edinburgh University’s Pro Bono Law Clinic, currently working on projects to make settled status applications for EEA nationals, and supporting Gypsy/Traveller communities in Scotland to access their legal rights.

Leah was motivated to write this blogpost after witnessing the effects of Glasgow’s first COVID-19 lockdown. The Unity Centre responded to the huge increase in demand for food by establishing a Direct Support team, which distributed food, medicine and other essentials to migrants across this city. While this response was hugely inspiring, and demonstrated the amazing power of collective organising, it was also a glaring symptom of an immigration system which consistently undermines fundamental basic rights.